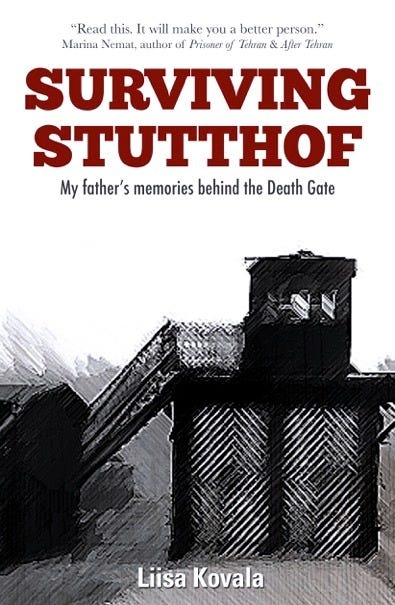

Cattle Car to Concentration Camp: My Father's WWII Journey from Merchant Marine to Stutthof Survivor

From book idea to publication and beyond.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, so I’m writing a series of posts about my father’s war experiences and our journey writing Surviving Stutthof: My Father’s Memories Behind the Death Gate together.

Week after week, I arrived at my parent’s 1950s bungalow, ready to record my father’s words about his wartime experiences as a young man, but it took months before he brought me to the Death Gate. He spoke about his life in Finland before the war, working as a sailor after the war, and moving to Canada in 1951. Sitting in his comfy armchair, a coffee in one hand and a chocolate chip cookie in the other, I wasn’t convinced my father would ever bring me through that Death Gate. But eventually, he did.

On September 21, 1944, my father, Aarne Kovala, was arrested alongside his shipmates in the Polish port of Gdańsk, then Danzig. Nazis marched the men, and a few women, down the cobblestone street to a warehouse where they were kept for some time, sleeping on the floor, and eating what paltry offerings were given to them. Eventually, they were relocated to a dance hall where they awaited their fate for several weeks.

In total, there were four Finnish ships: S/S Wappu, S/S Ellen, S/S Mercator, and S/S Bore VI and ninety Finnish sailors, of whom twelve were women. At sixteen, my father was one of the youngest sailors amongst the crew.

"Liisa Kovala's Surviving Stutthof is an act of true love … The book's direct, straightforward language puts the reader in the middle of history and how it can devastate good, ordinary people who are forced to face atrocities that are difficult to fathom. Read this. It will make you a better person."—Marina Nemat, author, Prisoner of Tehran & After Tehran

The Nazi officials tried to cajole the sailors into joining the German forces, but the Finns refused. As a result, they were shoved into cattle cars and sent on a slow journey to Stutthof (Sztutowo), about 36 kilometers from the port. It was the first concentration camp to be built outside of Germany and the last to be liberated. The crews were held for processing outside the infamous Death Gate, contemplating their fate, and fearing for their lives as they noticed the prisoners returning from work details, gaunt and frail, barely able to hold up their frames.

The telling of these terrible stories was not easy for him. As a stoic Finnish man, he rarely showed emotion, but I could see he struggled. I worried I would become to emotional, so I focussed on my laptop screen, typing notes as he spoke.

At some stage in our process, my mother mentioned he had always longed to visit the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. That summer, I booked hotel rooms, and rented a minivan. My parents, my mother-in-law, my husband and two children piled in with all of our luggage, and drove 1, 142 kilometres to Washington, D.C.

Once there, we were greeted by the brick walls and steel beams, and sunshine flooding the space. My father beelined it to the back of foyer where a woman—a fellow survivor—was seated.

“What camp were you in?” Nesse Godin asked after they introduced themselves.

“Stutthof,” my father said. He smiled his wide grin and his blue eyes sparkled. I’m not sure that he’d ever met a fellow survivor since moving to North America.

“So was I.” Nesse looked astonished. “I come here every week and meet lots of survivors, but almost never someone from Stutthof. People did not survive it.”

We soon learned they were the same age (both born in 1928) and were likely in the camp at the same time. Strangely, she only volunteered once a month on a Wednesday morning and here we had come all this way only to arrive on a Wednesday. My father and Nesse grinned, and cried, and hugged each other as if they were long lost friends. Before long, they had us all crying, including the staff.

I have such vivid memories of walking through the museum with my father, watching him explore every detail. But the most striking memory took place in a big room with only one item on display: a cattle car.

My father paused for a long time, staring at the cattle car. My mother-in-law gently suggested he could walk around it, if he wanted, but he shook his head. No, he needed to go through it. With tears in my eyes, I watched him enter, and pause within it, no doubt reliving those terrible memories of the journey to Stutthof. When he came out the other side, he was shaken, but held himself high, his cane in his hand. I had never been more proud of my father than in that moment.

While having my father’s story in book form is a fulfillment of a dream we shared, it’s these more intimate moments that I’ll remember forever. His courage to tell his story, his strength at facing his past, his vulnerability in the telling. His is only one story of millions of stories, some recorded, too many others forgotten. It’s a reminder how quickly the world can change and how anyone can be swept up into chaos and tragedy.

📚 At Women Writing, we’re marking the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II. Get a copy of Surviving Stutthof: My Father’s Memories Behind the Death Gate and receive a complimentary 6-month paid subscription to Women Writing with proof of purchase.

Happy writing!

I’ve been to that museum and I could hardly breathe, even though I had no close connection to the events. How amazing that your father met a fellow survivor. Thank you for this series!

Thank you so much for sharing this story. Beautifully written.